In today’s interconnected world, the staggering figure of $315 trillion in global debt might make one wonder if we owe money to extraterrestrial creditors. Of course, that’s not the case, but the real answer is nearly as complex and infinitely intriguing.

So, who do we owe?

When we hear that the world is $315 trillion in debt, it makes you wonder, who exactly do we owe all this money to? This huge amount isn’t just about big numbers; it’s about understanding who has lent this money and why it matters. From governments to businesses to everyday people like us, we all play a part in this story. Let’s dive into who holds this debt and what it means for all of us. To truly grasp the implications of this debt, let’s break down the main holders:

- Governments: A significant chunk of global debt is held in government bonds, purchased by a mix of domestic and international investors. These bonds fund everything from infrastructure projects to public services, impacting economic health and growth prospects.

- Corporates: Businesses, big and small, borrow to expand operations, innovate, and sometimes just to survive. This debt is held by banks, private investors, and other financial institutions.

- Households: From mortgages to student loans, household debt is what everyday people owe.

- Financial Sector: Banks and financial institutions themselves hold substantial debt, used to balance liquidity needs and leverage financial operations.

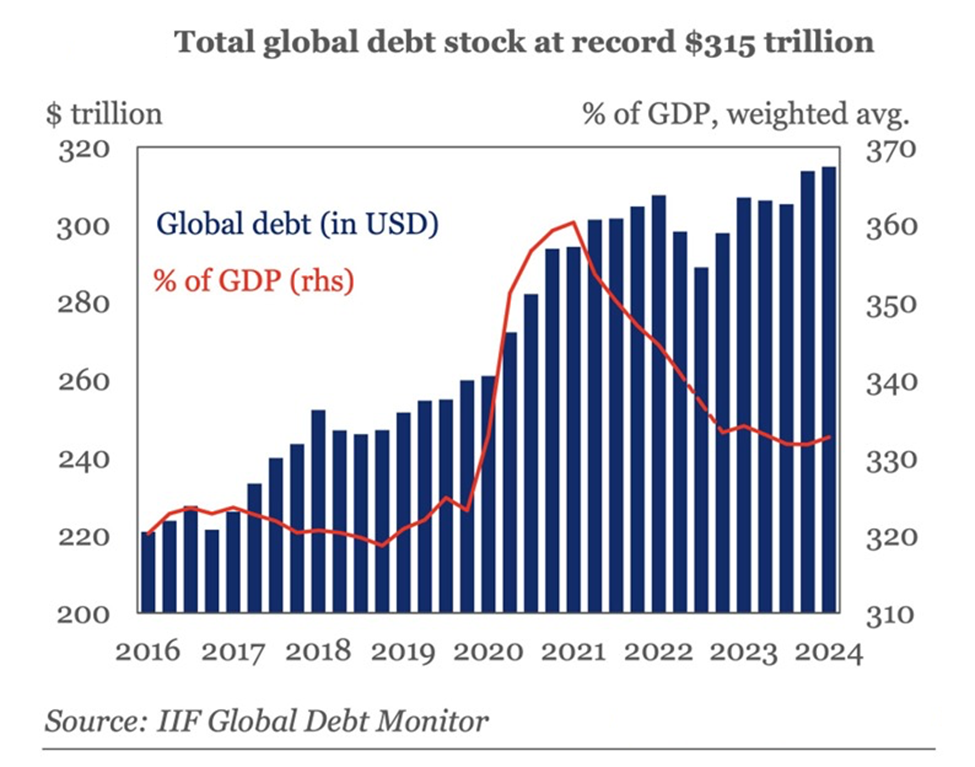

The total global debt has seen a steady increase from just over $200 trillion in 2016 to a record $315 trillion by 2024. The line graph (in red) representing debt as a percentage of global GDP shows fluctuating trends. Notably, there is a peak around 2020, likely due to the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, where GDP growth slowed, but debt issuance soared to fund stimulus measures.

After the peak in 2020, the debt-to-GDP ratio shows a decline, suggesting a recovery phase where GDP growth might be outpacing the rate of new debt accumulation. However, it appears to stabilize rather than continue decreasing, indicating that while the economy is recovering, high levels of debt still persist. This rising trajectory indicates expansive borrowing behavior across both developed and emerging markets.

Can this ever-growing debt truly be repaid?

As the global debt hits a whopping $315 trillion, it gets you thinking—can we actually pay all this back? It’s not just about big numbers; it’s about whether it’s even possible within the way our economies are structured. So, let’s dive into how money and debt work together and chat about if there’s a realistic path to getting these debts cleared up.

Understanding the Debt-Money Relationship

The world’s debt significantly surpasses the amount of money in circulation, with global ratios varying markedly by country. For example, Japan and Switzerland show a debt-to-money supply ratio of about 1.7, whereas Denmark and Iceland’s ratio spikes to 4.7. On a global scale, this ratio stands at approximately 1.8. Such high public debt relative to money supply is often deemed unsustainable by economic models, prompting economists to instead consider debt in relation to GDP. This ratio ranges from as low as 0.55 in Australia to a high of 2.61 in Japan, with a global median of around 0.62.

The Mechanism of Credit Money

The reason debt exceeds the available money is linked to how banks create credit money. When banks issue loans, they generate both credit money and corresponding debt simultaneously. This process initially boosts both the total societal debt and money circulation. However, as loans accrue compound interest, the debt grows while the “credit money” does not increase proportionately. This discrepancy primarily arises from the accumulation of interest on bank credit.

Theoretical Repayment Scenarios

- While it might seem daunting, the repayment of all debt is theoretically possible if banks reinvest the interest income back into the real economy, thereby allowing money to circulate and be reused for further interest payments. However, critics argue that too much capital is retained within the financial sector rather than being spent in the real economy, which could potentially lead to a perpetual increase in total debt.

- The situation could improve if the economic growth rate surpasses the interest rate on debt. This scenario would make it feasible to gradually reduce the overall debt. Nevertheless, this outcome is often considered unlikely, especially since the rate of return on capital investments frequently exceeds the rate of economic growth. Furthermore, environmentalists argue that continuous economic expansion on a finite planet is inherently unsustainable.

- Another potential remedy is if inflation rates exceed interest rates, effectively diminishing the real value of debt. Yet, this approach is not without its drawbacks, as higher inflation can also escalate real estate prices and other assets, thus encouraging further debt accumulation. High inflation typically results in lower consumer confidence, higher unemployment, and overall economic instability.

Systemic Financial Risks

The persistent growth in global debt is symptomatic of a financial system characterized by unbalanced growth between money and debt, often with inadequate democratic oversight. This imbalance tilts public and private interests, leading to economic instability and heightening the risk of financial crises. The fallout from these crises often disproportionately impacts the broader public through increased bankruptcies, unemployment, and housing evictions, while the financial sector tends to reap the benefits during boom periods.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the issue of repaying the towering global debt is not just a matter of economics but also of strategic financial management and policy-making. While the theoretical frameworks suggest potential pathways to manage and possibly reduce the debt, practical application remains fraught with challenges. Economic growth, reinvestment strategies, and inflation management appear as viable solutions, but their effectiveness is dependent on careful balance and foresight.

No comment yet, add your voice below!